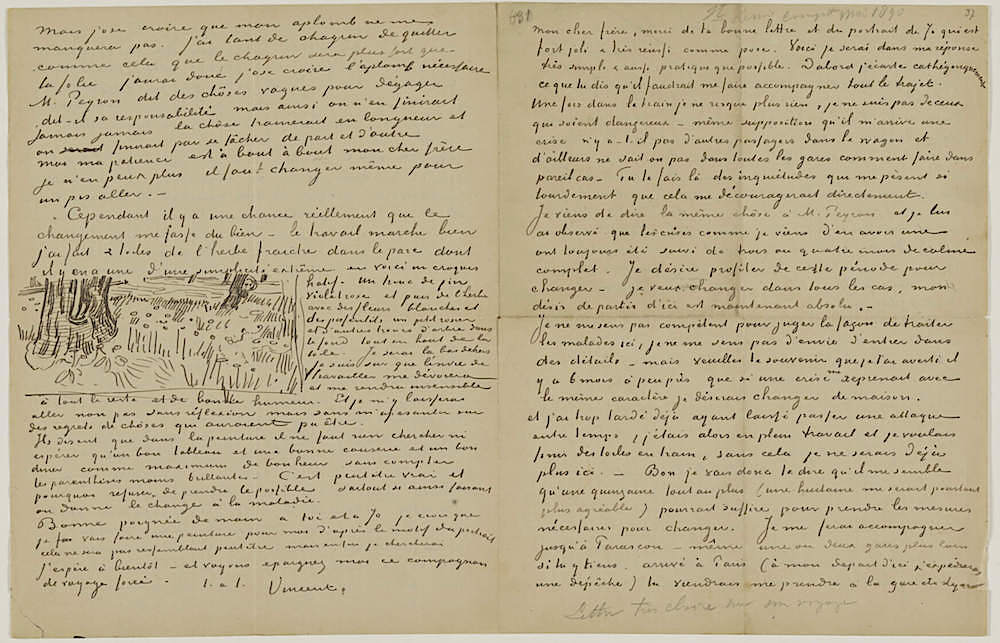

Letter 05/04/1890 - by Vincent van Gogh

My dear brother,

Thank you for your kind letter and the portrait of Jo, which is very pretty & a very successful pose. Now look, I'm going to be very straightforward in my reply & as practical as possible. First,

I categorically reject what you say, that I must be accompanied the whole way. Once on the train, I will be quite safe, I am not one of those who are dangerous - and even supposing I do have an attack,

there are other passengers in the carriage, aren't there, and anyway, don't they know at every station what to do in such cases? You have so many qualms about this that they weigh me down heavily enough

to discourage me completely.

I have just said the same thing to M. Peyron, and I pointed out to him that attacks like the one I have just had have invariably been followed by three or four months of complete calm. I want to take

advantage of this period to move - I must move in any case, my intention to leave is now unshakeable. I do not feel competent to judge the way disorders are treated here. I don't feel like going into details

- but please remember that I warned you about 6 months ago that if I had another attack of the same kind I should wish to change asylums. And I have already delayed too long, having allowed an attack to go

by in the meantime. I was in the middle of my work then and I wanted to finish the canvas I had started. But for that I should no longer be here. Right, so now I'm saying that it seems to me that a fortnight

at most (although I'd be happier with a week) should be enough to prepare the move. I shall have myself accompanied as far as Tarascon - even one or two stations further on, if you insist When I arrive in

Paris (I'll send a telegram on leaving here) you could come and pick me up at the Gare de Lyon.

Now I should think it would be as well to go and see this doctor in the country as soon as possible, and we could leave the luggage at the station. So I should not be staying with you for more than, let's say,

2 or 3 days. I would then leave for this village, where I could stay at the inn to begin with.

What I think you might do one of these days - without delay - is to write to our future friend, the doctor in question, 'My brother gready desires to make your acquaintance, and preferring to consult you

before prolonging his stay in Paris, hopes that you will approve of his coming and spending a few weeks in your village in order to do some studies; he has every confidence in reaching an understanding

with you, believing that his illness will abate with a return to the north, whereas his condition would threaten to become more acute if he stayed any longer in the south.'

There, you write him something like that, we can send him a telegram the day after I arrive in Paris, or the day after that, and he would probably meet me at the station.

The surroundings here are beginning to weigh me down more than I can say - heavens above, I've been patient for more than a year - I need some air, I feel overwhelmed by boredom and grief.

Also the work is pressing, and I should be wasting my time here. Why then, I ask you, are you so afraid of accidents? That's not what should be frightening you. Heavens above, every day since I've been

here I've watched people falling down, or going out of their minds - what is more important is to try and take misfortune into account.

I assure you that it's quite something to resign oneself to living under surveillance, even if it is sympathetic, and to sacrifice one's liberty, to remain outside society with nothing but one's work as

distraction.

This has given me wrinkles which will not be smoothed out in a hurry. Now that things are beginning to weigh me down too heavily here, I think it only fair that they should be brought to an end.

So please ask M. Peyron to allow me to leave, let's say by the 15th at the latest. If I wait, I shall be letting the favourable period of calm between two attacks go by, and by leaving now, I should have

the time I need to make the acquaintance of the other doctor. Then if the illness does come back in a little while, it would not be unexpected, and depending upon how serious it is, we could see if I can

continue to be at liberty, or if I must settle down in a lunatic asylum for good. In the latter case - as I told you in my last letter, I would go into a home where the patients work in the fields &

the workshop. I'm sure I'd find even more subjects to paint there than here.

So remember that the journey costs a lot, that it is pointless [to provide an escort], and that I have every right to change homes if I wish. I am not demanding my complete liberty. I have tried to be

patient up till now, I haven't done anybody any harm, is it fair to have me accompanied like some dangerous animal? No, thank you, I protest. If I should have an attack, they know what to do at every

station, and I should let them get on with it.

But I'm sure that my nerve will not desert me. I am so distressed at leaving like this that the distress will be stronger than the madness. So I'm sure I shall have what nerve it takes.

M. Peyron won't commit himself, because he doesn't want to take the responsibility, he says, but that way we'll never, ever, get to the end of it, the thing will drag on and on, and we'll end up by getting

angry with each other. As for me, my dear brother, my patience is at an end, quite at an end, I cannot go on, I must make a change, even if it's only a stopgap.

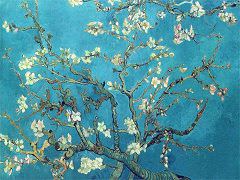

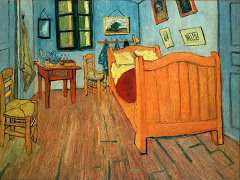

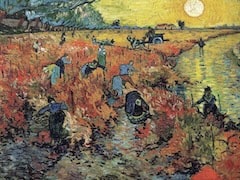

However, there really is a chance that the change will do me good - the work is going well, I've done 2 canvases of the newly cut grass in the grounds, one of which is extremely simple. Here is a hasty

sketch of it - a pine trunk, pink, and purple, and then the grass with some white flowers and dandelions, a little rose bush and some other tree trunks in the background right at the top of the canvas.

I shall be out of doors over there. I'm sure that my zest for work will get the better of me and make me indifferent to everything else, as well as put me in a good humour. And I shall let myself go

there, not without thought, but without brooding over what might have been.

They say that in painting one should look for nothing more and hope for nothing more than a good picture and a good talk and a good dinner as the height of happiness, and ignore the less brilliant digressions.

That may well be true, so why shouldn't one seize the hour, particularly if in so doing one steals a march on one's illness?

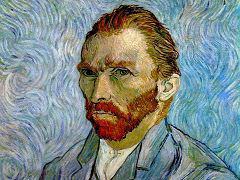

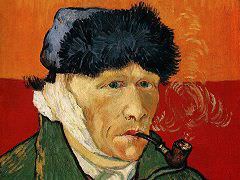

A good handshake for you and Jo. I think I shall do a painting for myself after the portrait, it may not be a resemblance, but anyway try. See you soon, I hope - and come on now, spare me this imposed travel

companion.